Sarcoidosis Program

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease that can affect any organ in the body, but most commonly affects the lungs. People with sarcoidosis have abnormal masses called granulomas that can cause the organ to change or stop working right. While there is no cure, sarcoidosis is a chronic disease that can be managed to minimize organ dysfunction.

The Sarcoidosis Program at National Jewish Health in Denver is the largest in Colorado and the Rocky Mountain Region. Our team of specialists works with you to manage your sarcoidosis and improve you quality of life. Because our doctors are researchers, too, you have access to the latest sarcoidosis clinical trials and most effective treatments.

A great pleasure for me to be able to introduce my dear friends and colleagues, Dr. Lisa Maier and Dr. Clara Restrepo, and they will be presenting our Grand Rounds today entitled, A Guidelines-Based Approach to the Complex Sarcoidosis Patient.

We're going to start the program with Dr. Lisa Maier, and we're going to be taking questions at the end in the Q&A box, not the chat box.

As many of you know, Dr. Maier is the Division Chief of Environmental Health Sciences and OCMED here at National Jewish.

She also holds the rank of professor in the Department of Medicine here and at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, as well as the School of Public Health.

Dr. Maier wears many hats, but she wears them very well. She guided many institutions through the pandemic.

She is a world-renowned expert in Borreliosis, but she is an international rock star in sarcoidosis.

People clamor to see and talk to her at the national meetings, and I've personally seen this at ATS and CHEST.

She was part of this special program from the 9-11 firefighters who developed sarcoidosis after the Twin Towers fell.

She is amazing, and we are so excited to have her here today.

Dr. Maier, the floor is yours.

Lisa Maier, MD, MSPH:

Thank you, Jinny.

That was way too gracious, and I really appreciate it and back at you.

So we're going to start off.

I'm just going through our disclosure slides, and as Jinny mentioned, Clara and I are going to be sharing the floor today.

As I was telling Vamsi and Jinny, this is the last Friday of Sarcoidosis Awareness Month, and we were lucky enough to start with the grand rounds in April on the first Friday on sarcoidosis and excited to be doing this one also today.

Our objectives are really to review two recent guidelines that outline diagnosis and evaluation first, as well as another one that looks at treatment approaches, and also give you some clinical pearls as we go along here.

So I was lucky enough to help co-chair this ATS, Diagnosis and Detection of Sarcoidosis Official Practice Guideline that was published right as the pandemic started in April of 2020, again, was saved for Sarcoidosis Awareness Month, and now I'm excited to talk to you about a lot of the real little tidbits that are present that hopefully can help you as you think about these, as well as other similar patients.

So as most of you know, sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease, and many people will call it the great masquerader, as it can involve any organ, and it really doesn't have a classic manifestation per se.

It's also a diagnosis of exclusion, and so the problem therein is that we don't have a gold standard, and because of that, actually, it can take, on average, months to years, and up to 14 years in one study for, as the upper bounds, for patients to get a confirmed diagnosis.

And this makes it very hard for folks, not only from a standpoint of them feeling comfortable with what they have, but also for us as physicians to figure out how to treat them.

We know that some organs can be more difficult to diagnose, and part of that is because of limited access.

You know, we have the luxury of being able to access the lung pretty easily with bronchoscopy, but the heart and the neurologic system can be much more difficult to try to get a biopsy or even sample tissue. And then the disease heterogeneity is a problem.

Again, this is a disease that has many, many different phenotypes, and I often tell my patients that we have to continue to re-diagnose or reassess the diagnosis on a regular basis as they have new symptoms and potentially as we want to consider if other organs are being involved.

Just to point out here, this is a classic CT of somebody with sarcoidosis, with lymphadenopathy, conglomerate mass, as well as these classic nodules following the bronchovascular bundle.

This patient also had splenic involvement, and you'll also see that her PET scan is highlighted here in her liver.

So she also had a lot of abdominal involvement in addition to having pulmonary involvement.

So I'm going to use a case presentation to kind of walk through some of the points that I want to emphasize with you all.

Again, I don't expect anybody to answer these questions.

They're really here for us to talk through different points.

This is a patient that actually was sent to me by one of the folks in pulmonary who came in with pretty asymptomatic pulmonary disease, normal lung function, and a CT scan, again, with some nodularity and some lymphadenopathy, not clearly as abnormal as that last one we saw, and had no other evidence of extra pulmonary disease.

So the questions that he and I discussed first was, did he need a biopsy?

And the questions that I will tell you is that here's some different answers.

Yes, he needs a biopsy, and he needs a mediastinoscopy.

He doesn't want a biopsy, and you agree that for right now he doesn't need treatment, so we can continue to wait and watch.

He doesn't want a biopsy, and you tell him he must have one because we have to confirm disease.

Well, this is actually, I think, highlighted by a problem that came up with the 1999 sarcoidosis diagnostic guidelines, and that is that those were an expert opinion based on extensive review of the literature, and the intent was never that a biopsy was required for all patients, and yet that was the interpretation.

And so again, they established a diagnosis or diagnostic criteria being that people would have a clinical radiographic compatible picture, a biopsy showing non-casein granulomas, and exclusion of other diseases.

The one exception to this, even in this guideline in 99, was that if you had Lofgren syndrome, a biopsy wasn't needed, but again, many people assumed based on that guideline that you had to have a biopsy.

And so in the 2020 guidelines, we used a different approach versus expert opinion.

We used GRADE.

We used PICO questions.

So patient or population, intervention, the comparer group, and outcome to address a number of questions, primarily centered around follow-up actually, an initial evaluation, but two centered on diagnosis, and then two centered on cardiac sarcoidosis evaluation if you had suspicion for cardiac sarcoidosis.

Again, we said that compatible clinical presentation, if granulomatous inflammation was present, but not always required, and you could exclude alternative diagnoses, this was a reasonable diagnostic.

These were reasonable diagnostic criteria.

Again, a lot of this ATS guideline supports that we need a lot better, higher quality evidence to guide our clinical practice.

Again, most of the studies that we were looking at were observational.

They came from specific centers.

They weren't representative of the U.S. population.

A lot of them were quite old also.

And so again, we really need more data was the bottom line that came out of this 2020 statement.

Now, just when we talk about a clinical picture that's supportive of a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, Lofgren's is the easy one, right?

Someone has lymphadenopathy.

They have erythematodosum and arthralgis.

We don't see a lot of that here in the U.S.

We see some, but it's not that common.

There are some other tips and tricks that you can find on physical exam like lupus pernio, which is involvement with the nose, as well as some imaging findings, some of which we discussed and other abnormalities like finding hypercalcemia or hypercalceria in the setting of abnormal vitamin D metabolism.

There are a number of findings that suggest probable sarcoidosis and again are worth at least considering together.

I would say that many of us still push for a biopsy if we think treatment will be indicated, but for the patient like the one we just discussed, probably don't need to get a biopsy.

Okay, here's some follow-up for our case.

So after doing well for a couple of years, he starts to have persistent cough and his lung function is now declining.

So what do you do?

Do you refer him to a surgeon for immediate stenoscopy or vats?

Do you do a bronchoscopy and just get transbronchial lung biopsies, maybe trying to get that mass or some of those nodules?

Or do you do an EVAS or do you do an EVAS and transbronchial biopsy?

And this really was the basis of the first couple of PICO questions that we had.

And I'm just going to walk you through some of the data that actually is available and present to help you understand if you're interested where the, you know, what actually was done and how we approach these questions.

So we had a number of methodologists who reviewed some of the articles that the librarians, we had both Chandra and I and Liz Kallemeier involved in this one.

And for this particular question, they found 700 and some articles, the methodologists decided to review 64 and felt that 29 were appropriate for this study.

And then based on that, they would do some meta-analyses.

And so let me just tell you that there were no EVAS compared to immediate stenoscopy studies available in sarcoidosis.

And so that's a big problem and probably gives a significant bias.

A lot of the immediate stenoscopy studies that outline sarcoidosis as a diagnosis were very, very old also and didn't, and probably had differential follow-up from the ones that are more recently done.

Again, what they would do is to say if we have a hypothetical 1,000 patients and we know that we would get adequate specimens for most of them, about 961, the diagnostic yield, so from that 961, 830 or about 83%, we could get a diagnostic biopsy.

And then from those, we could go ahead and get a diagnosis of sarcoidosis in the vast majority in 801 versus an alternative diagnosis.

Now, media stenoscopy, I mentioned to you that none of these were compared to sarcoidosis and we don't have all of the information that we did on the sarcoidosis population, although we do know that the vast majority who had a suspicion of sarcoidosis were diagnosed.

Now, again, I think that might be a bias of those studies.

So after we got that data, we sat in a group and discussed the results.

And what we discussed, what are some of the complications?

So for EBIS, they didn't have any major complications reported, and they actually did a more thorough job of reporting complications in many of those studies.

Overall, it's only 0.1%.

We really thought that the risks of media stenoscopy were underreported and underrepresented.

They reported very serious ones, but not potentially less serious, but consequential.

For example, a complication that we frequently see is vocal cord damage after media stenoscopy, and that wasn't reported and yet can impact quality of life, costs, as well as lung function for some folks.

We also reviewed some systemic reviews that recently were conducted.

And there were nine studies where they looked at media stenoscopy for cancer.

Again, not sarcoidosis, but they did find more side effects, as most of us have seen.

They also talked about that if you added transbronchial biopsy, if there were radiographic abnormalities, that you might increase the yield, and some of the studies suggested that.

And that's actually what we recommended.

If you're in there already and you don't get a definitive diagnosis on EBIS, you may want to get some transbronchial biopsies.

We also said if you don't have EBIS available, but you have blind TB and A, that might be something you could consider.

So these were some of the other comments that came out in our discussion and that we provided in the recommendations for the ATS guidelines.

So overall, our summary for the first question was we thought there was an advantage of EBIS because we could get the diagnosis in 87% of the patients.

The vast majority of those would have sarcoidosis, although not all of them, and that the risk of that procedure was much less than the risk of the 13% that may require a second procedure.

So again, our recommendation was for suspected sarcoidosis, if somebody has lymphadenopathy and tissue sampling is necessary, that's the big part, then those people should undergo

EBIS over mediastinoscopy as the initial lymph node sampling procedure.

This was a conditional recommendation with very low quality of evidence, and I will tell you that the vast majority of the recommendations, if we made them, were in this category where they weren't very high quality.

For each of the questions, we also outlined research needs, and a couple that we thought about were, look, if there are specific CT or chest X-ray manifestations, could that help further improve either the diagnostic yield or people that maybe need instead to go to another type of procedure?

It would be great if we could have a biomarker that could be coupled with a biopsy to help us at this juncture, too.

Now, we also looked at some additional recommendations for biopsy, and one of ours was when can you maybe not do a biopsy?

The point was, if you have a high clinical suspicion of sarcoidosis, we talked about Loughgren syndrome, we talked about the lupus perneum, then maybe those are the conditions.

Hereford syndrome is one where you end up with parotid or salivary gland enlargement, facial nerve palsy, and also anterior uveitis.

We don't see that a lot, but again, if you have those, those are pathognomonic for sarcoidosis, and you don't need to do a biopsy.

You really need close follow-up unless something changes in those people.

Now, if somebody has asymptomatic bilateral hyalurlipadenopathy, there's been a discussion and there's some older articles that some of us learned about when we were in medical school that suggested maybe you don't need to biopsy, folks.

And I will tell you that we came down to saying that we couldn't make a recommendation for or against.

Part of it was this tree here, where if you had a thousand suspected patients, 854 could be diagnosed with sarcoidosis based on lymph node sampling, 35 had an alternative diagnosis, and that was usually lymphoma.

And so I think folks felt that while this is a small number, it's still clinically super important.

And so that's where we ended up saying that, you know, if you decided against sampling, close follow-up is needed, but we did not provide a recommendation for or against.

And again, the research needs were, it would be helpful to better understand natural history and predictors for some of these diseases to help us maybe find more phenotypes that might not need a biopsy.

Now, there's a figure that we put into the guidelines, and it's this clinical presentation, and it's kind of an algorithm of when do you need to think about a biopsy over here and when maybe don't you.

And if you don't get a biopsy, what might be some alternatives that you might want to consider?

So I'm just showing you that for your reference for the future, if this comes up.

Now, as I mentioned, we had six of our 10 PECL questions were geared toward evaluating other organ involvement, extra pulmonary disease.

And this really was focused because of the literature on initial screening. I'll tell you that there is not a lot of data on follow-up for patients for sarcoidosis.

We could find articles, most of which were quite old, all of which were observational, so very low quality of evidence, to address screening for kidney involvement, liver involvement, hematologic disease, cardiac disease, and abnormal calcium and vitamin D metabolism.

And you'll see some interesting pieces here.

And again, these are the recommendations that we made, although, again, when we get a chemistry panel, for example, we're going to get a number of the other tests that aren't listed here.

So renal disease, we did recommend a baseline creatinine, liver, alkaline phosphatase, but not transaminases.

Now, there was a lot of discussion that, A, we get a lot of false positives, if you will.

Our patients can have fatty liver.

They may have other reasons for having abnormal transaminases.

We often get them before we start treatment.

And yet the committee did not feel that they could make recommendations because abnormal transaminases usually weren't associated with abnormal or liver involvement in sarcoidosis.

A CBC was recommended, not because it really helps us to find hematologic involvement or even spleen involvement, but because in young women, many of whom are the ones that are being diagnosed more commonly than men, anemia can be important and it can contribute to pulmonary disease.

We did recommend a baseline EKG, again, noting that a lot of the abnormalities that we find on EKGs are actually not related to sarcoidosis, but to see if there were abnormalities that developed.

We recommended against an echo or a holter as an initial evaluation asymptomatic, again, asymptomatic patients.

We did recommend checking vitamin D levels, 25 and 125, before somebody started supplementation.

And that's because there's actually been, the one reasonable study, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial that showed that people actually could develop renal failure, albeit it was reversible if they were supplemented with calcium and had abnormal vitamin D levels or were supplemented with vitamin D.

We did make a strong recommendation for supplement calcium, checking calcium.

And that was because, again, we know high calcium levels can be associated with renal failure and that those who are detected and treated actually can have reversible kidney disease.

Whereas if you don't detect high calcium levels in the setting of renal failure, that it can be less likely to be reversible from a renal standpoint.

So I'm going to try to move to the next slide.

So as I mentioned, the issue of follow-up and getting yearly tests, there really is no data on this.

And so this was expert opinion.

And again, this is a table that we included for folks as reference.

And I will tell you that this is what the committee came up with and there was some discordance here.

And I will tell you that our clinical practices vary too.

So for example, many of us do get annual chemistry panel or even CBC, and yet we did not end eye exams.

We didn't recommend that.

And because the data really suggested that if you have problems with vision, people are going to have symptoms and that's going to help trigger it.

But we often also need eye exams to help us evaluate side effects of treatment, whether it's hydroxychloroquine or steroids.

For pulmonary hypertension, again, we didn't recommend specific testing, although we do have two or three questions that I'm not going to discuss today, in which we did say if people have signs and symptoms, that then yes, an echocardiogram can be useful.

If that's abnormal, then a right heart cath may need to be considered.

And so again, I'll let you look at those.

So let's come back to our case.

So more recently, after we went through and we did establish a diagnosis of sarcoidosis based on an EVAS, he started having increasing shortness of breath, palpitations, and had an episode of presyncope.

He was found to have atrial arrhythmias by a cardiologist.

And so the question now is, if we're worried about what would be symptomatic, not asymptomatic sarcoidosis, what testing should we do?

Should we get an endomyocardial biopsy, a cardiac MRI, a cardiac PET, or none of the above?

So again, this was part of a couple of our questions focused on actually evaluation of suspected symptomatic cardiac sarcoidosis.

And the question really came down to, do you use a cardiac MRI or a cardiac PET or an echo?

Now I can tell you there were 2,400 articles on this topic, and yet you can see the number here in the top that really were appropriate for review.

11 for cardiac MRI, 6 for PET, and 2 for echo.

And I'm not even going to review these because they were really pretty poorly conducted.

And there were no studies that had all three well designed.

There's a couple that had some hints about it.

But if you look at these various studies, and these are, again, some of the analysis that our methodologists did showing a sensitivity and specificity, for example, for cardiac MRI.

And we know that overall, we've found that these tests showed abnormalities in 27% of the patients that were evaluated, and they were associated with increased cardiac mortality, overall mortality, arrhythmias, FERT failure, cardiac events, sudden cardiac death, with reasonable sensitivity and specificity overall.

Cardiac PET, abnormal in 52%, only associated with increased cardiac event, trend towards mortality.

And again, you'll notice that the sensitivity and the specificity aren't quite as good as what we see for cardiac MRI.

So our recommendation was for extracardiac sarcoidosis that we would recommend a cardiac MRI over a PET and both of those over echocardiogram.

Now again, as I mentioned, it's difficult to compare the accuracy of these modalities because there's no reference standard, there are lack of studies in large cohorts comparing them.

They actually may be telling us some different information, and our cardiology colleagues frequently point that out to us.

MR may be telling us more about scar, and PET more about inflammation.

And the question is whether the two might be complementary.

However, I do think many of us worry about cardiac PET giving false positives, and I think most of us in the sarcoidosis clinic can show you some examples of when that's happened.

So again, as I mentioned, cardiac MRI preferred over echo.

If it's unavailable, then cardiac PET over echo, and it's a conditional recommendation with very low quality of the evidence.

So the outcome of our case, actually, this patient ended up having a cardiac MRI, and he had abnormalities that are consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis, and Dr. Restrepo is going to talk about treatment for pulmonary and extra pulmonary disease, so I'm not going to keep talking about that.

Now, I just want to give you kind of my 10,000 foot view on some of the benefits and limitations of this ATS statement.

First of all, again, the last one published was more than 20 years old, so it's really good to have an update and to use evidence-based assessments, even if the quality of the evidence overall was pretty low.

Again, I think we really tried to clarify and reiterate that a biopsy may not always be needed to make a diagnosis.

We did address screening for organ involvement using evidence as much as we could.

We looked at pulmonary and some cardiac outcomes.

We didn't have the ability to look at every other organ, and Dr. Tavi, I'm sorry, we didn't look at neuro, something still to be done.

It was a multidisciplinary panel, and now the ATS has a mechanism to update this every five years.

Now, the limitation is, again, we even looked at cardiac disease, for example, in a pretty limited manner.

Again, I mentioned the data and the bias.

We also had a lot more pulmonary experts, although we did have a couple of cardiac folks involved.

We also had a more U.S. versus international panel, and we know, for example, that disease really varies across the globe.

For example, in Japan, they get a lot more ocular and cardiac involvement, and so, again, those are issues that these may not universally apply to other groups across the globe.

And again, we didn't make treatment recommendations, but luckily, we can now turn this over to Dr. Restrepo.

So, Claire, if you want to take control of the screen, I'll let you do so.

During this time, I'm going to go ahead and introduce Dr. Restrepo.

She is the head of the sleep lab here at National Jewish, as well as the head of the clinical

operations in oc health and environmental sciences here at National Jewish.

She holds the rank of associate professor in the Department of Medicine.

Before she was here, she was actually the chair of the respiratory section at St. Joseph's Hospital, as well as the director of the ICU for over 10 years over there.

But her most impressive title came before that, when she was Lisa Maier's senior resident at Duke, where they were born, bred, and raised.

Can you imagine telling Dr. Maier to go downstairs and do the admit at two in the morning?

Anyway, she has been taking care of sarcoidosis patients for many years.

We've shared several over the last decade.

She is a fantastic clinician.

Her patients love her for that, as do we.

So, Dr. Restrepo, please.

Clara Restrepo, MD:

Thank you, Jinny.

You are always too kind.

So, I'm going to focus on the treatment part of this talk and, again, go through some of the European Respiratory Society.

And I want you to come out of this talk thinking when you see a sarcoidosis patient within these three parameters, who do you treat, when, and how to treat.

And I'm going to start with a case that I saw.

This poor woman was 42 years old.

She had three years of cough before she finally got seen.

She was a former smoker.

She had some nodules at the time of presentation.

But because of her abnormal chest imaging and a biopsidical non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, as we saw from the diagnostic portion of this talk, that actually gave her the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

This is actually a current image, so it's not quite as when she presented, but there's clearly some upper lobe changes consistent with previous granulomatous inflammation.

Unfortunately, this woman started on prednisone well.

She started on prednisone in 2016.

She may have had some hydroxychloroquine initially, primarily for the skin nodules, but this poor woman has remained on 30 milligrams of prednisone for four to five years.

When I saw her, her symptoms included dyspnea.

She had gained 100 pounds.

She had polyuria.

She had clear symptoms of sleep apnea, significant fatigue, arthralgias, and low extremity edema.

And she had a body mass index of 44 and a significantly elevated blood pressure.

So right off the bat, we start with a woman that has untreated hypertension, obesity, type of ventilation syndrome, sleep apnea, mild cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 50 to 55 percent, diastolic dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension with RVSP of 45.

She was significantly hypoxic.

Fortunately, she didn't have any evidence of bone density abnormalities, and she didn't have any diabetes at the time that we started seeing her.

And her lung function was markedly abnormal with both some restriction and some obstruction.

And this is, I wanted to choose this case to highlight the issues that we have with treatment in this population and hopefully get you a little bit better framework for how to decide on treatment for these patients.

But clearly, steroid treatments is associated with significant problems.

And here's a study from the 1990s from our rheumatology colleagues that delineate that even low doses of prednisone can be associated with significant adverse events.

This is just, she already exhibits many of these treatment outcome problems that are possibly known.

So what is even more terrifying is the study from 2020 that even low doses of steroids can be associated with significant or was associated with significant increased risk of all cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, aphid

cerebrascular disease, even at one year, although a lot of these patients do have other comorbidities that can contribute to them.

But probably some of these are also being made worse by the steroids.

So what about in pulmonary sarcoidosis management?

So studies have shown that probably 20 milligrams of prednisone or less is necessary.

And in this study from Bruce from Europe, even at three months, we do not have any good correlation between the dose of the steroid and the percent FEC change.

And a percent FEC change is a primary endpoint of many of the treatment trials in sarcoidosis, even though it's not necessarily the best because we have phenotypes that are different in pulmonary sarcoidosis.

But I want you to see that there is no significant correlation.

So higher doses of prednisone may not be associated with better outcomes.

And in this, the same group did another study that even at four weeks, you can see a signal primarily the major signal from the dose of steroids, you can start seeing at four weeks and you don't see any further changes after three months.

So extending the treatment trial is not necessary.

So think about that.

So who do we treat?

Usually the organs that get involved that have the highest mortality and morbidity include cardiac, neural and lungs.

And even though 90 percent of the patients present with pulmonary involvement, only about 40 to 50 percent may need treatment.

A significant proportion of patients may present with, for example, liver involvement, but this is the minority of patients that need treatment.

So when you think about who needs treatment, keep that in mind.

And I will sort of summarize this at the end of the talk.

So let's talk about these guidelines that were they came out in last year in 2021.

And as Dr. Maier said, the last set of guidelines was from 1999.

The methodology was the same for some of these questions.

They actually had thousands of articles pulled and the majority of the questions really only had a few number of articles that were actually a fair of fair evidence.

Like Dr. Maier said, most of the questions also had either very low quality of evidence or low quality of evidence.

So they had eight patient intervention and comparison outcome questions that were addressed with 12 recommendations that came out of them.

Two were for pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Two were for cutaneous sarcoidosis, one for cardiac, one for neuro.

So there we go.

At least it's being addressed, Jinny.

And the last two PICO questions were related to syndromes that affect our patients in a high proportion and have a high symptom burden for them.

So let's talk about pulmonary sarcoidosis.

I'm just going to first have you look at this outline in that in this outline, they do have some recommendations and algorithm for patients with intermediate risk and low risk, but the data available was not really significant to make any recommendations.

And so all the pulmonary recommendations are really related to high risk patient.

What does high risk patient, what does a high risk patient mean?

It's usually a patient with progressive pulmonary disease, major pulmonary involvement, significant physiology, physiologic abnormalities, or quality of life implications.

And so the first question was, should you treat, should you start gluco corticoid therapy versus not?

And so the recommendation is that for untreated patients with major pulmonary involvement that you think is high risk, that you should consider steroid treatment to improve and or preserve either force vital capacity and quality of life.

Again, the force vital capacity is a primary employee for many of the treatment trials, which is why they chose that.

And sometimes we don't necessarily see that much of a signal, but sort of keep that in mind that that's the recommendation.

It was a strong recommendation.

It was a low quality of evidence.

The next question was, well, what about the person that continues to have significant pulmonary involvement and continues to be at high risk and may or may not have significant or unacceptable side effects from steroids?

The suggestion is to add methotrexate.

That's the only, out of the studies that they saw, methotrexate was the only one that had some evidence, although the practice does include other medications such as azathioprine, lufunamide, mycophenolate, and even hydroxychloroquine.

This is a conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence.

That's the first part of that question.

The second part was, if you continue to have significant disease burden, continued issues with pulmonary involvement, and they've already been on some of these drugs, then to suggest and consider additional infliximab.

Yes, we do also use adalimumab, but there's less quality of evidence, and so that couldn't be recommended.

This is a conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence.

Now, let's move on to the next couple of questions, which are related to cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Cutaneous sarcoidosis, I would probably say that this is the minority of the patients that we see in our clinic, but the majority of the time, you usually start with topical steroids.

It usually means that there's cosmetically important or a significant high burden of disease that is affecting multiple areas to the point where topical steroids is not feasible.

The question is, should you consider adding steroids versus no steroids?

That's the first question, and this is what they recommended.

If the disease burden is high or you have cosmetically important involvement, then yes, consider adding an oral glucocorticoid to the management.

What dose of glucocorticoid?

Usually, these patients also end up on lower doses of steroids.

The second or the fourth question, pico number four, was if the patient continues to have significant organ involvement, significant cosmetically burdensome disease, and you've tried immunosuppressive therapy, so they didn't actually answer this question in the middle, but the assumption is that people have progressed to another immunosuppressive agent should you add anything else versus remain on steroids.

That actually was the recommendation that they came up with was to add infliximab.

Both of these conditional recommendations, low or very low quality of evidence.

The next question, I'm going to spend a little bit more time because this is actually a high mortality and significant question that we see in our clinic is cardiac sarcoidosis.

Cardiac sarcoidosis can be complex.

Patients obviously can have high risk.

Let's talk a little bit about who gets cardiac sarcoidosis.

This is actually the reverse of the primary findings in that we tend to see the odds ratio are increased in whites versus blacks, and it actually tends to be more common in males versus females. They tend to cluster. They can cluster with ocular and neurologic involvement, so if somebody presents with neurologic disease, optic myelitis, you should be very careful and aware and ask about cardiac symptoms. It is the one appearance, the one organ involvement that can appear decades after the diagnosis.

It may affect two to five percent of sarcoidosis patients in some studies, but at autopsy, you can actually see sometimes between 25 and 30 percent of patients may have involvement of the myocardium. How do they present? AB block is the most common.

Bundle branch blocks can also be seen. AB blocks tend to be the most probably responsive to therapy.

They can also present with cardiomyopathy, and we believe that that's probably either a a result of high burden of disease or chronicity enough to affect cardiac function.

They can present with malignant arrhythmias, and there's some debate about whether supraventicular arrhythmias are really related to sarcoidosis or not, but there's probably the minority of the arrhythmias that we see in sarcoidosis. And this table actually comes from the ERS guideline paper that you should look at prognostic variables that may influence treatment.

So because of the morbidity and mortality, patients that are older, that have cardiomyopathy, that have high functional classes or very symptomatic, that have diastolic dysfunction, that have abnormalities on imaging such as cardiac MRI, cardiac PET scan, in Europe they do use this global longitudinal strain, and there may be some signal there for following. This is just being reported on echocardiograms, but they actually include it in this table of prognostication, and then maybe some even evidence of myocardial injury or heart dysfunction, and clearly people that have ventricular arrhythmias are at high risk of needing and requiring therapy. What doses? The studies have not shown that more than 0.5 milligrams per kilogram were any more effective than less than or equal to 0.5 milligrams per kilogram. So be aware of this. You don't need to be putting patients on high doses of steroids and know that heart block may be the most responsive to therapy.

We tend to think that cardiomyopathy patients may be less responsive, but do know that sterile withdrawal may be associated with worse outcomes. So the question that they were trying to answer was in patients with evidence of functional cardiac abnormalities and significant cardiac disease, should you start steroids with or without other immunosuppressive agents versus no immunosuppressivation, and this is kind of where the recommendation landed. There is nothing for the other immunosuppressive agents because there's not enough evidence, but definitely the recommendation is to at least start steroids. I will tell you that in our practice we believe that cardiac disease does not go into remission quickly, and therefore we usually tend to start other immunosuppressive agents to be steroid sparing early on.

And you can actually see the rest of the algorithm, which is sometimes what we end up doing, is that these patients continue to have disease and we end up having to use tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. I thankfully have not had to use cytoxin, although I know Dr. Maier has had patients that have had progression and require further treatment with cytoxin, and sometimes they actually require transplantation. So moving on to neurosarclerosis.

And symptomatic neurosarclerosis can actually be seen in 5 to 20 percent of patients. It is highly associated with significant morbidity, mortality, disability, so it is a presentation that often requires treatment. So when they looked at the data, should you start immunosuppressive agents versus no immunosuppressive agent, these were the questions and the recommendations that came out of that question. I will tell you that the cranial, so presentations that can involve, that can end up with neurosarclerosis involvement include cranial neuropathies are very common, but you can have granulomatous inflammation in any part of the nervous system. And so what I want to stress is that this is actually due to granulomatous inflammation in the brain, in the spinal cord, in the meninges, or even on the peripheral nerves. So for that question, should you start steroids, the recommendation is if there are clinically significant findings, yes, you should start steroid treatment. That's a strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence. The second piece of this algorithm, and there is actually an algorithm in the guidelines that you can look, the second question is if patients continue to have treatment there on steroid therapy, the suggestion is to add methotrexate. Yes, we can't, we have used other medications such as mycophenolate and azathioprine, but the quality of the evidence is not there to make it a strong recommendation, although that's probably what most of us do. It is a conditional recommendation, it was very low quality of evidence. And then the third recommendation is that if you are on steroids, if your patient is on steroids and immunosuppressive therapy and they continue to have disease, then there's a suggestion to add infliximab. It is a conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence, although I'm going to put a plug into it because Dr. Taddy gave us a talk and I've learned this. There is a couple of trials, they're retrospective, infliximab may be starting earlier on, may be associated with better control of disease quicker, and there are reports of high relapse rates when infliximab is discontinued. It can be as low as three to 12 months, and hopefully Jeanne can add some to that later on.

The next two recommended questions were really related to, like I said, these are issues that our patients get plagued with. They're a high disease burden for them, and unfortunately the data that we have for treatment is very poor. Fatigue is a very common complaint in sarcoidosis patients. Up to 90% of patients can have this disease. Immunosuppressive therapy may not have an effect. The question that they asked was, should you treat fatigue with any therapy versus no therapy? They actually came up with two recommendations in that if you can, and you have found usually when we have patients with sarcoidosis or fatigue, fatigue can be a multifactorial symptom, and so we do a complete evaluation to see if there are any other disorders such as sleep disorders that can contribute to fatigue. If you don't find anything that is necessarily treatable, the recommendation that they actually had was pulmonary rehab or inspiratory muscle training may be helpful to try that for six to 12 weeks. These recommendations were conditional, low quality of evidence, and the second recommendation is that if you have done immunosuppressive therapy and pulmonary rehab or inspiratory muscle training and they continue to have sarcoidosis-associated fatigue, meaning there is no other cause than you may consider methylphenidate or armadaphenol, which is a stimulant.

There are drugs used in the sleep world to help stimulate weightfulness, but they may be useful in sarcoidosis-associated fatigue and to try them for eight weeks.

This last question was about small fiber neuropathy. Small fiber neuropathy is probably the bane of

Dr. Tavi's practice. We see a significant number of patients. It can occur in up to 40 to 60 percent of patients. It is a high morbidity, high disability kind of associated problem.

These patients present with significant paresthesias. They can actually have autonomic dysfunction that inhibits their bowel and bladder function, sweating, orthostatic hypotension, and so they actually may have other significant issues that affect their quality of life.

The small fiber neuropathy is not thought to be related to the granulomus inflammation exactly on the nervous system, but it's actually an effect of the inflammatory process and the,

I call it the evil humerus, the cytokine milieu that may be affecting the peripheral nerves.

It tends to be more common in whites and females, and so the question that they asked was, should you do any immunosuppressive therapy versus IVIG versus no therapy? Sorry, I missed that out there. Unfortunately, there was no good evidence to make a formal recommendation, although we are lucky to have Dr. Tavi, which is one of the experts, and she actually has done and written studies about Infliximab and IVIG, maybe helping some of these patients. So that is something that we try, but a lot of times we need to just treat the symptoms, and we are hoping that at some point we can get better treatments for these patients.

So going back to my patient, first, do no harm. You know, 30 milligrams of prednisone for that extensive period of time is not ideal. Think about who, when, and how you treat them. Think about the organ involvement. Usually we think about is there a danger to the organ compared to what symptoms are being caused? Usually it is easier when you have higher danger of organ, for example, in cardiac sarcoidosis, to start immunosuppressive therapy, although sometimes we struggle because it may not be as symptomatic. So these other quadrants sometimes require more thought, but I would actually add that there is another dimension to this, and it is the patient.

You need to involve the patient in the conversation about risk and benefit and whether you are actually helping them with the therapy. Personalize the therapy as much as possible. Use the lowest possible dose of steroids and even other immunosuppressive agents. Assess for continued need, and then again involve your patient. In the ERS, there is actually this table about the drugs that we use and the doses that are usually used that can be useful as a reference.

As Dr. Maier has always said, we need help. We need trials and sarcoidosis treatment because the quality of the evidence is poor. We need to address the racial and gender disparities that affect some of these patients, and if you heard Dr. Sharpe's talk, this was addressed in that talk. We need better therapies than steroids. This is the only FDA-approved drug.

We need to span treatment and look at patients that have different organ involvements, and we need to really involve the patient because patient quality of life and how good patient reported outcomes is important. We are way behind the rheumatology and asthma colleagues in which their personalization of therapy is driven by biomarkers, and that's what Dr. Maier is working on. We ask you, this is a shameless plug, send them to our clinics or send them to centers of excellence so that we can study and formulate better trials. We are open for questions.

Thank you so much both to Dr. Maier and to Dr. Sharpe. That was an excellent and exhaustive review of the new guidelines on diagnosis and treatment. We do have two questions already from

Dr. Merrick, but please, just a reminder, put your questions in the Q&A box, not the chat, because that is recorded. The first question by Dr. Merrick, and this can be for both of you, we can certainly start with Dr. Restrepo. Why is infliximab recommended rather than any of the other anti-TNF antibodies? It really is only because the evidence, the articles have been, there's more evidence with tumor necrosis with infliximab. Adalimimab can be used, but there are some studies with others like uskanimab and gamalimab that were not helpful.

And so it's usually we use either infliximab or adalimimab.

Dr. Maier, do you have anything to add to that? No, I just think it's the evidence. There may be some data also that with the adalimimab, for example, that folks with sarcoidosis need a little bit of a higher dose than maybe some of the other diseases. And so sometimes we have to go up on the dose for it. And I would say even in infliximab, we often don't start it every eight weeks, but we'll start every four to six weeks. So again, it may be a difference in the disease biology, but we don't really know. I know in the world of CNS sarcoidosis, especially with brain and spinal cord sarcoidosis, infliximab, there have been now, so there are no randomized clinical control trials in neurosarcoidosis. The numbers are just too small. So we have, if you look at all the data, there are just over 200 patients who have been recorded to have infliximab and the treatment outcomes, and they do great. This is the best treatment we have for CNS sarcoidosis.

And in my personal experience of patients over the last 20 years, adalimimab does not cut it for them. And most neurosarcoidosis neurologists will treat with infliximab. As for... Oh, go ahead. No, I was just going to say, I think cardiac is also the data supports it more, again, observational only. The second question from Dr. Merrick was, can you comment on the usefulness of rituximab? I know Dr. Boffman loves rituximab, but Lisa, why don't you go ahead and start with that one? Yeah. So again, we talked about low quality of data. In rituximab, there's been very few studies. I think there are some indications that it's used kind of after even infliximab. And if there are specific indications, some folks seem to like it more, again, a vasculitic type of response, which we occasionally see in this disease. It does seem like it works. It doesn't seem to be as helpful, again, with the limited data in, for example, cardiac disease. And Jenny, you can certainly tell us about neuro, but I know it's not always your first go-to there either. It's never our first go-to. So Clara, I don't know if you have anything to add to that. I think it's kind of like last-ditch effort, too. Right. It's probably third, fourth down on our list of drugs to try if we have poor control with other agents.

Right. And I agree. It's the vasculitic paradigm that we use it for. We have a monitoritis multiplex that we used it for. And I remember Stacey Clardy from the University of Utah. She's a well-known neuroimmunologist. I remember at a meeting for a neurosarcoidosis specialist, she raised her hand.

She goes, can we all agree that ritoxan doesn't work for CNS sarcoidosis? All hands up. And so we all raise our hands. But the next question is from Dr. Edward Chan. When do you get 24-hour urine for calcium? Wouldn't it be more sensitive and specific than serum calcium to support sarcoidosis? So I'll give it to both of you. Yeah. So, you know, the guidelines, we actually looked at urinary calcium, and the data was not great, was part of the problem. But I would say, clinically, we will usually get both a serum and a urinary when people are initially evaluated.

And if folks are found to have some problems, that's one that we follow up in. Yes, Ed, as you're indicating, we often will see abnormalities more with the urinary calcium than the serum.

Another time would be if people have kidney stones, wondering if it's contributing to. And Clara, I don't know if you have anything else to add to that. Yeah, usually it's, I think if anybody has had kidney stones, we certainly think about doing that. I also think about it when the vitamin D125 is high, because then there will be increased risk of hypercalceria. What I find a lot of times is that this also helps me with bone health prevention, especially if people need to start on therapy, just because I think that they're probably going to be at higher risk of osteoporosis if their urine calcium are extremely high. So.

And we don't have any more questions, but I do have one question for both of you, just because, you know, you touched on it with the vitamin D causing renal failure.

What is your recommendation for vitamin D repletion in patients?

I would say that, you know, in the past, we in the sarcoidosis world have been very reluctant to give people vitamin D replacement. And I think that's a problem. I mean, I think that, again, for those folks that have been on prednisone a long time, you know, we should be following guidelines. Certainly, if they have osteoporosis with this phosphonates, which clearly have been shown to improve on density. And I think our colleagues in rheumatology help us with some of those folks. It's the folks that are kind of in between that can be hard. But that's where I think, again, replacement is needed in this group. I've heard about some cases of people developing rickets because they've developed, you know, vitamin D deficiency. And so I think that, you know, again, checking it before you put people on and then after you put people on, if they are deficient, is important. But it's the 125 you got to check, because if that's normal, then they're good to go. Right. And remember that the 125 is the much more effective and active form of the vitamin D. And I also think of it as almost like a disease marker, right? Because if your vitamin D25 is extremely low, oftentimes it's because of the granulomas inflammation and the hydroxylase that's been secreted by the granulomas that are probably driving that vitamin D25 low when you have a normal vitamin D125. So before we start supplementing people that have, because they have very low vitamin D25, you should check the vitamin D125. That's a great recommendation.

Well, I don't see any more questions, but I wanted to thank you again, both of you, for an outstanding talk on how we can diagnose and treat sarcoidosis. Thank you very much to both of you. Thank you. Thank you.

WASOG Sarcoidosis Center of Excellence

WASOG Sarcoidosis Center of Excellence

National Jewish Health is one of just a few facilities in the world to earn recognition as a World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases (WASOG) Sarcoidosis Center of Excellence. This designation provides formal recognition of our team’s commitment to meet the needs of sarcoidosis patients and efforts to keep abreast of the ongoing advances and findings in the space.

Doctors

-

Shu-Yi Liao, MD, MPH, ScD

-

Lisa A. Maier, MD, MSPH, FCCP, ATSF

-

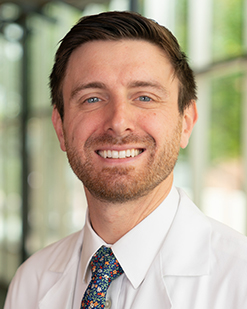

Mark Mallozzi, MD, MPH

-

Clara Restrepo, MD

-

Raphael Sung, MD, FACC, FHRS

-

Jinny Tavee, MD

-

Kalie M. VonFeldt, PA-C, MS

-

Howard D. Weinberger, MD, FACC

-

Daniel Zank, MD

Clinical Trials

Clinical Trials

- Biomarkers & Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Progression

- Creating Asthma Measurements through the MORRE Study

- Healthy Adults Needed for Beryllium Disease Study

- Healthy People Needed for Sarcoidosis Research

- Identifying Characteristics and Patterns of Asthma

- Immune Pathways & Development of Sarcoidosis

- Investigational Gene Therapy for Adults with CF

- Lung Injury from Military Deployment

- New Trial Medication for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

- Predict and Prevent Lung Disease

- Predicting ILD from Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

- Pulmonary Fibrosis & Genetic Factors

- Silicosis Registry

- Skin, Airway & Esophageal Epithelial Barriers in Youth

Reasons to Choose National Jewish Health

- The leading respiratory hospital in the nation and the only one devoted fully to the treatment of respiratory and related illnesses

- Ranked #1 or #2 in Pulmonology by U.S. News & World Report for 26 consecutive years

- Ranked in the top 5% of hospitals in the nation by HCAHPS

- Physicians consistently recognized among the best in the nation by multiple services, including Best Doctors in America and Castle Connolly

- Among the top 6% of organizations funded for research by the NIH, providing patients access to hundreds of active clinical trials

- 124-year history of focus on care, research and education serving patients from around the world with lung, heart, immune and related disorders

Little Body, Big Battle

“I’m thankful that we were able to come and get tested because we would have never known. We would have probably never gotten the treatment that Ivan needed.”

Read More