What’s Behind the Recent Rise in Tuberculosis Cases?

A recent outbreak of a disease most people think of as eradicated is attracting new attention to a notorious illness. In Kansas, dozens of cases of tuberculosis (TB) have put health officials on alert and raised questions about further infection.

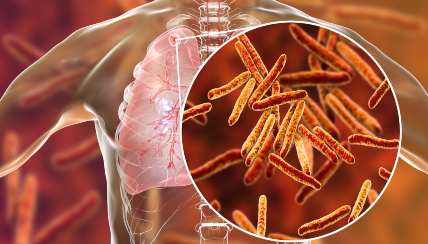

Over the past few years, there has been an increase in the number of TB cases in the U.S. In the late 1800’s, TB was referred to as “consumption,” an illness with no cure that was running rampant. TB is a lung infection that results in coughing, fever, weight loss, night sweats and occasionally chest pain, among other symptoms. If left untreated, TB can be fatal.

Treatments emerged in the mid-20th century, coupled with public health funding for contact tracing and other strategies that decreased the number of people with active TB. Then, with the onset of the HIV pandemic, the number of people with active TB again began to increase, as living with HIV and being immunocompromised is a major risk factor for TB. When treatment for HIV emerged and people were able to recover immune function as more robust systems for infection control developed, TB began to decrease to several thousand each year.

Given TB’s historic impact on public health, changes in the number of people with active TB are constantly monitored by experts, including infectious disease specialist Michelle Haas, MD, who was able to shed some light on the reasons behind the recent rise in TB cases across the U.S.

COVID’s Role

While the recent increase in cases have been alarming, Dr. Haas explained that the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed, as many people went undiagnosed. “There was a fairly sharp dip in the number of people diagnosed with TB globally in 2020,” said Dr. Haas. “Additionally, the movement of resources to help deal with COVID led to a lack of resources for TB. When people finally were being diagnosed with TB, you could tell that their TB was more advanced.”

The masking practices adopted during the pandemic also may have contributed to lowering the spread of TB in other countries according to Dr. Haas. “Surgical masks are effective at stopping droplets from the mouth, which is one of the main ways TB is transmitted,” she said.

Dr. Haas explained further that masking probably had very little impact in the U.S., where there is almost no community transmission of TB. Whether this had an impact globally and within communities where TB is more common is uncertain at this point.

Likelihood of Widespread TB Infection

Even though increases in TB cases are worth monitoring, Dr. Haas noted that physicians and researchers aren’t seeing evidence of broader transmission. “In these cases where there’s a surge in numbers, such as the recent outbreak in Kansas, it's mostly delays in diagnosis,” said Dr. Haas.

In fact, she explained that there is currently really no community transmission of tuberculosis in the U.S. Part of that is because there needs to be a certain number of people in a community with TB before widespread transmission occurs. To be infected, a person also has to spend a lot of time with someone who has active tuberculosis. “When I say a lot of time,” she explained, “I mean usually about eight hours. So it's very different from COVID where you could get exposed in 15 minutes.”

Even though TB infections are unlikely to return to the rates seen by Americans during the late 1800s, Dr. Haas stressed that having public health institutions was crucial to keeping TB at bay. “There's always the chance that there can be an unraveling of public health,” said Dr. Haas. “We've been in an okay place with TB, but if we lose the ability to do contact tracing and provide care for people with TB, that will change. It’s important to find everyone with TB and connect them with care. If that doesn’t happen, we would start to see an increase in people with TB here in the U.S.”

Dr. Haas expressed grave concerns about the recent discontinuation of funding of USAID and PEPFAR programs, which have abruptly shut off care for millions of people with TB and HIV globally, risking dramatic increases in people becoming ill and dying from TB, including children. Current estimates are that deaths secondary to TB may increase by 2.2 million over the next 5 years. Drug-resistant TB cases may increase by 30% globally, which would require medications that are difficult to procure. Some are not FDA-approved for use in the U.S.

Dr. Haas shared that we are likely to feel that impact in the U.S., where it can cost $154,000 dollars per person to care for someone with drug-resistant TB. Additionally, interruptions in the CDC staff’s ability to meet has led to interruptions in clinical trial updates for TB, TB consulting and attendance at national meetings for updating TB care. Dr. Haas sits on a TB clinical trial protocol team that has been unable to meet since the pause on CDC activities. The recent cuts to NIH funding also will impact the ability of TB scientists to conduct research to advance TB care, including here in Colorado.