Wildfire Health Effects

How to Protect Your Lungs and Heart From the Effects of Wildfires

When you think of wildfire damage, you might picture forests — and increasingly homes — caught in a fast-moving blaze. However, there’s another important element at stake.

“You can rebuild a house. You can’t necessarily rebuild your lungs,” according to pulmonologist Anthony Gerber, MD.

As wildfires become more severe (Opens in a new window) and widespread, it’s important to understand how airborne pollution from these fires can affect your health. This knowledge is crucial even when you appear to be out of harm’s way.

Why Are Wildfires Getting Worse?

Since 1983, the wildfire problem in the western U.S. has been growing (Opens in a new window). Wildfires that impacted more developed areas such as the 2021 Marshall Fire (Opens in a new window) in Colorado near Denver and the 2025 L.A. Fires are just two examples. Climate change, drought and previous forest management practices have contributed to the issue.

It’s a problem Dr. Gerber doesn’t see going away anytime soon. “There is model after model that predicts hotter summers and more sporadic rainfall,” he noted. New home construction is piling even more fuel on the fire. “We now have this increasing tendency to build up into the wildlands,” Dr. Gerber explained. "And so we’re seeing urban encroachment in areas that are simply more at risk for wildfires.”

This means that the devastation from wildfires includes more homes and personal property. And when synthetic materials burn, the health effects of wildfire smoke can be more severe.

The Particulate Problem

When something burns, it’s broken down, and its elements are released into the air, often combining with oxygen. The carbon from burnt matter can take the form of carbon dioxide (as carbon atoms bond with the oxygen).

Heavy, prolonged exposure to the carbon dioxide/monoxide in smoke can have a smothering effect. However, with a wildfire, especially one that burns homes and other structures, there are a lot more unknowns.

“You wouldn’t throw a battery onto a campfire,” explained Dr. Gerber, “but that’s what’s happening. When homes burn, along with cars and other things, you incinerate all of this material. It’s hard to quantify, but that stuff is almost certainly more toxic. Also, the chemicals that are sprayed to put out the fire were designed for use in forests, not in urban areas. Although necessary, they add to the toxic impacts of wildfires that occur in populated areas, such as the 2025 Los Angeles area fires.” It is particularly distressing when you think of your computer, television and even refrigerator going up in smoke.

Dr. Gerber emphasized that the plume we see from a nearby wildfire is actually a particulate soup. It is peppered with toxins released from industrial materials. Plastic, for instance, produces sulfur dioxide and hydrochloric acid when burned, along with heavy metals (Opens in a new window).

An EPA-led study (Opens in a new window) on toxic particulates showed that plastics produced the most harmful emissions. Burning plastic is more toxic than plywood, cardboard and even diesel fuel. When inhaled, these particulates can cause a range of breathing problems, especially if you have a preexisting condition.

The Western U.S is the most affected by wildfire smoke. The West tends to have drier summers. It has more forests, and it just tends to have longer and more intense wildfires. The heart of the season is really the summer and early fall. Wildfire smoke generates what we call particulate pollution, and particulate matter pollution is dangerous. It's small. It gets inhaled deep into your lungs. There's a local reaction to it, and sometimes that local reaction can cause body-wide inflammation. Not all wildfires are actually just burning trees. That smoke can contain burnt plastics, burnt metals. If batteries are burning, it can be a really toxic mix of chemicals, and then when you breathe it in all those different things can make it very inflammatory.

The most important conditions that are impacted by wildfires in terms of pulmonary disease would be asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is what people think about as smoking-related lung disease. Then also interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis. If you look at wildfire pollution and risk of heart attack or stroke, we will see that in response to particulate matter pollution, there's an increased risk of having those events. We ask people to look at the air quality warnings, and on the very worst days where it says it's unhealthy for everyone if you could modify your activity, maybe not exercise outside particularly in the late afternoon when the air quality is worse. That's definitely something we recommend.

The other advice that we give people is related to indoor air quality. So for some people, in their house if they keep their windows open, the air quality inside can wind up being very similar to the air quality that is outside. If people have a HEPA filter which will help keep that air quality inside cleaner. If they can afford to run their air conditioning, those strategies can at least keep the indoor air safer to breathe.

Climate change is making wildfires bigger and worse. What we can do individually is to try and reduce our footprint of greenhouse gas emissions, but we can also be mindful that other pollutants (so just normal gas-fired cars, trucks, a lot of these things which also generate particulates). If we can limit the use of those kinds of equipment and machines, that'll put us in a better position to deal with the inevitable increase in pollution from wildfire smoke that we're going to see now and over the next 10 to 20 years.

How Wildfires Can Affect Your Respiratory and Heart Health

Smoke can worsen symptoms for those who have preexisting respiratory conditions, such as asthma, allergies and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Typical symptoms may include:

- Cough with or without mucus

- Chest discomfort

- Difficulty breathing normally

- Wheezing and shortness of breath

“Pretty much any preexisting lung condition can be aggravated by breathing in these particles,” according to Dr. Gerber. “You’re living with your normal asthma symptoms, and then suddenly you may have a decline. That decline might be manageable with inhalers, but sometimes it requires medical attention.”

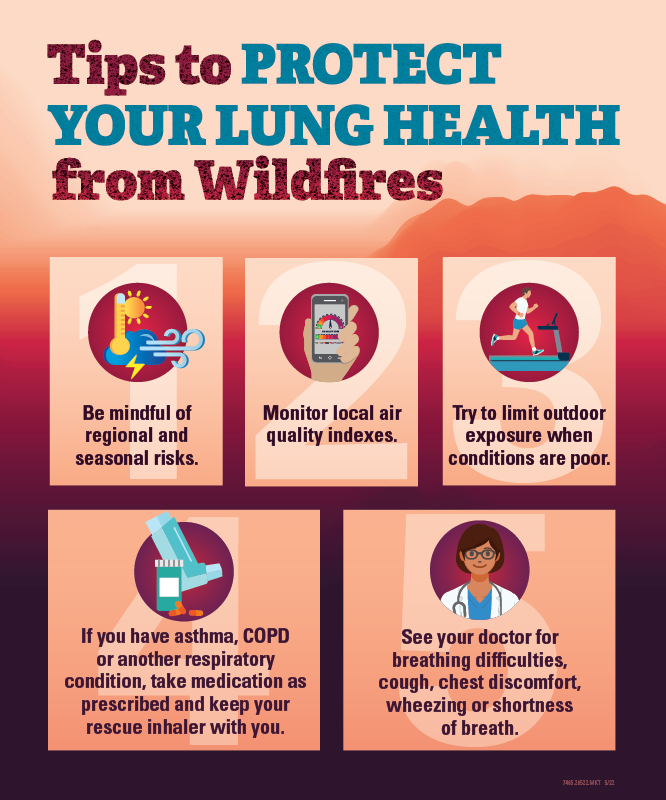

If you have a lung condition, it’s important to monitor local air quality. Be aware of any wildfires in the region.

Particulate-laden smoke also can worsen heart disease. Inhaled particles trigger the release of chemical messengers into the blood, which may increase the risk of blood clots, angina episodes, heart attacks and strokes. People with chronic heart conditions are more susceptible to chest pain, heart attacks, cardiac arrhythmias, acute congestive heart failure or stroke.

Even people without lung or cardiac disease may become symptomatic if the smoke is thick enough.

Do Wildfires Increase the Risk of Heart Attacks and Strokes?

Scientific evidence published by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) shows that exposure to these toxic particles increases everyone’s risks for heart attack and stroke. This risk for heart attack and stroke increases even if you don’t have a preexisting lung disease. The EPA says that even if you’re only exposed for a few hours, it can affect your health.

People without lung diseases aren’t as used to tracking air quality. They are perhaps less likely to avoid exposure to wildfire smoke and to notice its effects on their systems. “You may never realize that, ‘Hey, I might be more at risk for a heart attack two days from now because I was out in the pollution,’” said Dr. Gerber. “So it’s another major problem that tends to really get lost in the shuffle. We don’t pay attention to it.”

Long-Term Effects

For people with prolonged exposure to wildfire smoke, such as firefighters and other safety personnel, long-term respiratory problems could be seen down the road. Smoke inhalation, long working hours and scorching temperatures all contribute to health concerns. In these cases, wildfire smoke exposure could result in decreased lung function, although these effects could be reversible. The proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is paramount to mitigating the effects of smoke exposure.

Why is wildfire smoke harmful? Learn about how wildfire smoke affects people with respiratory and allergy conditions, and people who are directly fighting the fires from National Jewish Health Allergy and Immunology Expert, Flavia Hoyte, MD.

Recommendations for Wildfire Smoke Exposure

If wildfire smoke is triggering mild symptoms, National Jewish Health doctors recommend that you:

- Take medications as prescribed, and use a rescue inhaler if one has been prescribed.

- Do not take more medication, or take more often, than prescribed.

- If you are near the fires where smoke or particulates are significant, or if the smoke is making you sick, consider leaving the area until the air is clear again.

- Stay indoors as much as possible, and close windows if you can.

- Limit or eliminate outdoor exercise until the air clears.

If you require increased medication or are experiencing increased symptoms, contact your doctor to decide whether you should be seen.

High Temperatures

It's important to stay indoors as much as possible when the smoke is pluming from wildfires. It may be difficult to stay inside during the hot weather, but the use of full-house attic fans can help to lower the temperature throughout your home. A whole-house or window unit air conditioner, or a swamp cooler, is also a good cooling appliance.

High summer temperatures and low humidity can fuel wildfires, making the smoke and particulate matter (PM) hang in the air even longer. Particulate matter in the air can cause breathing problems for those with lung disease or who are prone to respiratory problems. Avoiding prolonged exertion can help prevent worsening symptoms. To determine the amount of PM in the air, check your local air quality advisories.

Air Quality Advisories

Air quality advisories are conducted by your local Department of Public Health and Environment. These advisories can help you better assess the outdoor conditions and whether you should be going outside.

Colorado Air Quality Advisories (Opens in a new window)

HEPA Filters

One way to limit exposure to airborne allergens and irritants is the use of a High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filter. These filters can be effective for people who have problems with airborne allergens and irritants such as wildfire smoke. HEPA filters are available in room air-cleaning devices and for use on vacuum cleaners. People who use HEPA air filters say they feel better and have reduced symptoms.

Types of HEPA Filters

Freestanding filter units trap airborne allergens, such as pollen and animal dander, and don't re-release them back into the air. HEPA filters attached to vacuum cleaners reduce dust by trapping the small particles and don't re-release "dirty" air.

Many people with allergies, asthma, and chronic bronchitis have a freestanding HEPA filter in the bedroom, a HEPA filter attached to a vacuum cleaner, or both. Filters need to be changed regularly in freestanding units and vacuums.

When using a freestanding unit with a HEPA filter, designate one room in the house in which to place the unit to maximize the cleanliness of the air in that room all the time. Do not use a freestanding unit that produces ozone emissions (some of these units do). Ozone can increase with wildfires and high temperatures, further worsening the air quality.

Respirator Masks

Do not rely on dust masks for protection. Paper "comfort" or "dust" masks commonly found at hardware stores are designed to trap large particles such as sawdust. They often have one strap, but may have two. Dust masks, as well as surgical masks, will not protect your lungs from smoke.

An “N95” mask has two straps and will be stamped “NIOSH,” indicating it is a certified respirator. N95 masks also can be purchased at hardware stores. When properly worn, a well-fitting respirator mask can offer some protection. KN95 masks are less protective than N95s, but they also filter out some of the particles from wildfires.

Final Thoughts

Particulates and air pollution have always been a concern. However, the spectacle of wildfires shines a larger spotlight on the problem. “It’s so profound that I think it offers an opportunity for people to recognize the dire threats of climate change and the specific threat of increased particulate matter pollution,” said Dr. Gerber. Our knowledge in both areas is still evolving. It is his hope that the current wildfire crisis could eventually spark more public health education.